Modernism and feminism. The latter on the rise and the former falling fast. Both movements decisive for women architects. That is the scene of these two isms in architecture in India. Let me elaborate.

I say modernist architecture is losing face fast in India. Let me rephrase that. Some basic principles of this movement are under scrutiny. There are several reasons for this. If you are aware of the ongoings in the architecture sphere, you would know that ‘sustainability,’ whatever that term implies, is the talk of the town. And there is no soul who doesn’t know that concrete, steel, glass, etc, or the offerings of the Industrial Revolution, rank high on the carbon footprint index.

Another reason is that with a paternalistic perspective, modernism has little to no regard for the site, context, or culture of a region, as its very edicts proclaim. But we all know that ignoring a site’s context is not a sign of superior intelligence but downright stupidity. It has been some time since people have begun to recognize that fighting the environment is no wise move.

However, this doesn’t mean modernism should be thrown unreservedly down the metaphorical garbage chute. Certain principles of modernism are very sensible, especially in a resource-starved world. For example, housing the program should be among the top priorities of an architect. Also, the less material used, the better, at least when it comes to carbon-heavy materials like concrete.

The second movement I mentioned is feminism. Well, no one is a stranger to this term. But while gender equality and such notions have been thrown around for long, it is only in recent decades that this movement has taken root in India. And if we combine feminism with architecture, that span is even less. Women architects have not received the attention they deserve. Their works, truly sensitive and cultural buildings, have been pushed off the pages of Indian architectural history

In this article, I consider how women architects have come up in the industry through the 20th century and heading into the 21st, and what challenges they had overcome to get where they are.

Women architects in the British Raj

To tell this important story, we have to revisit the roots. Take the scene back 200 years to the 19th century to the British Raj in India. The industrial revolution is in full swing in Britain. Every scientist, artist, politician, and Tom, Dick, and Harry is just raving about how the march of science and the fall of the ways of yore is the most formative event to happen in human history. This tale pitter-patters down to India, the melting pot of a hundred cultures, the “jewel in the crown” of the British Empire.

Now, the British Empire is ever keen to show their superiority to their colonies. And they reckon architecture, or more precisely, the identities associated with it, is a hell of a way to do that. And so, slowly, architecture in India takes a turn, from vernacular forms of building to the modernist idiom. The previous statement might not read heavy, but its impact on the buildings of India was strong enough to change their fundamental identity, and hence the identity of India’s culture. The full extent of this is unraveling before our eyes today.

Now let’s fast track to the 1920s. Enter Mr. Gandhi. Well, not the person specifically. More so what the idea of him implies. Independence. Identity. Individualism. You get the point. We encounter the start of the women’s movement in India in the world-famous independence movement. Ravaged by the British Raj to the breaking point, Indians, under the leadership of Gandhi, converted what was a quarrel among high-class politicians into a mass movement. And in the middle of this storm, women came forward. As any slightly-acquainted-with-their-history Indian would tell you, women had a big part to play in the country’s freedom struggle. And it is this struggle that sows the seeds of rebellion against the status quo in the Indian woman’s consciousness.

Moving on to the 1940s, the freedom struggle is raging full on. At first, women were satisfied to rebel from their homes, but now, they come out under the public eye. They are not afraid to participate in marches and underground movements or even go to jail for them. The fire of feminism is beginning to spread rapidly.

Moving to the post-independence era, the entire world has noticed women now. At first, there is a backlash due to the assumed limited identity of a woman as a mother. Women are only being offered “feminine” jobs like sewing, nursing, etc. This continues for a few decades and we land in the 1970s. Women now occupy positions of power in the government and people begin to think that this gender might have something real to offer humanity other than popping children out of their wombs.

And now, let us come to the present. We know what is happening at the moment, don’t we? Prejudice and gender inequality have not disappeared but they are well on their way out.

Modernism in post-independence India

But, you say, that’s all good and well, but what’s architecture got to do with it? That’s what this blog is about, isn’t it? Well, I’m coming to that just now. Let’s point the spotlight towards the first prime minister of India, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. See, this guy wanted everything modern and nothing of the old. And it made sense too. If someone ravaged your homeland for nearly a century, you’d want everything to have a new identity, right?

And it was especially so with architecture because of all the sciences, it was the most tangible one. Thus, every Indian architect you met around the corner in the first few decades after Indian independence was raving about modernism. That was because modernism equaled secularism and that represented the idea of independence. And to aid this image, the master of modernism, Le Corbusier, landed in India in the 1950s for the lighthouse Indian post-independence architectural project, Chandigarh. And it was only a decade later that another master of the same school, Louis Kahn, washed up on the shores of India. We all know this guy’s influence in Ahmedabad.

In this interval, exposed concrete and bricks were never more than a stone’s throw away. Most of the architects of that period, like Charles Correa, C.S.H. Jhabvala, Balkrishna Doshi, and the like, had gone abroad for their education and come back with their heads filled with the ideas of the modernist movement. In this regard, women architects weren’t far behind. Women architects like Gira Sarabhai, Pravina Mehta, Urmila Eulie Chowdhury, and Minnette de Silva were also championing modernism.

Yet history confirms that unlike the total disregard of context that certain architects, whose names need no mention, showed, Indian architects, men and women alike, paid great respect to the site of a building. Despite what most people in the world thought at that time, Indians weren’t stupid Third World monkeys. A perusal of the earlier works of the mentioned architects would leave no doubt in any mind that those buildings are not slaves to modernist principles but more like tributes to its finer points. A proof of the previous statement exists in the abundance of brick jalis (screen), shaded verandahs, courtyards, and other vernacular elements created in their buildings.

And just like that, from the 1970s onward, modernism’s gnarly claw was twisting itself out of the collective Indian architect’s consciousness as the representative of progress. Even lay people could see that when a building responded to its site and culture of the region, it just became that much more functional and beautiful. People could see that craft-based traditions, like wood and metal work, or lattices and jalis were more than simple decorative elements: they had evolved over centuries and were deep insights into the cultural phenomenon of India.

The style that advocated this type of architecture was critical regionalism. In essence, it said that modernism’s “universal” principles were not so universal and must adapt to each region’s specific vocabulary. And women architects were on top of this.

Then a metaphorical bomb exploded on the Indian scene which accelerated the women architects’ movement and significantly turned the direction of architecture. This bomb was the economic liberalization of 1991. India threw its economic gates open to privatisation and socialism took a back seat. No longer was the government dictating the majority of the architectural projects in the country, which admittedly had its limits in terms of an architect’s creativity.

Now, multinational companies and conglomerations were hankering for private architectural projects. In such projects, money was often not a constraint. Plus, there were a dozen new building technologies on the market now. An average architect in India in the 1990s would be like a kid in an unexplored Lego store. And as far as women were concerned, they now held jobs in all sectors, though not without their share of prejudice.

Women in architectural education

Let me dispense with a myth about architecture school. Unlike our mostly indolent engineering college brethren, we architecture students have our noses stuffed with work in college. No wonder it is at this stage that we learn some of the most essential elements of this field. Given that this is such an important milestone, we must discuss gender equality and women’s role in architectural education in general.

Let’s briefly revisit the past. The first college to offer a professional education in architecture was the now-famous Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai, established in the 1920s. However, the word “professional” conveys the wrong idea. Under the British Raj, the only aim of Indians’ education was so they could provide manual labor. Architectural education under colonial rule in India was set up with one goal: to serve engineering. That’s a downright insult to the profession, in my opinion.

Even in the post-independence era, it took almost a decade before different architecture departments were set up. It was only from the 1970s onward that more colleges popped up across the country.

But let’s increase the pretty quotient of this article by turning our attention to women’s architecture education. A pretty fair idea can be imparted through statistics here. In the 1920s, you’d only find one or two women in the entire batch of Sir J.J. School of Art. Fast forward to the 1960s, in the same college, among some 30 odd students, you’d spot five or six females. In the first decade of the 21st century, women are equal in number to men in architectural education.

But these statistics are one side of the coin – the students’ side. Let’s flip the coin and see what’s up on the staff side. Things don’t appear so egalitarian here. Rarely would you find a woman to be a department head in an architecture college. Nor do people of this gender appear much in student juries, inauguration guest panels, interview panels, or college inspection visits. Even in national associations like COA (Council of Architecture) or IIA (Indian Institute of Architects), few women board members can be spotted.

When it comes to the actual education itself, things are even more unbalanced. Rarely do students study the works of women architects. 99 percent of the role models students are expected to look up to are males. The professors themselves are not much educated in this area, though to be fair, not much material can be found either. The judgment is clear: while women’s participation in architectural education itself ranks as high as men, or higher, the same cannot be said for architectural practice. This is the topic we turn to next.

A look at India’s master women architects

The story you read about the progress of the women’s movement through the 20th century will now make sense. Because it parallels the same movement in architecture. As women’s voices grew louder through the decades of the 20th century, so did their participation in the architecture industry. Let’s name a few names.

Perin Jamshedji Mistri (1913-89), hailing from the Parsi community in Mumbai, acquired a diploma in 1936 from Sir J.J. School of Art. She joined her father’s firm M/s. Ditchburn, Mistri, and Bhedwar in 1937 and eventually became a partner. Until two days earlier, I hadn’t heard of her even though she did some great work.

Urmila Eulie Chowdhury (1923-95) graduated from Australia in 1947 with an architecture degree. She worked with Le Corbusier in Chandigarh and made some fine architecture herself. Yet, beyond Delhi and Chandigarh, a scant few have heard of her.

Pravina Mehta (c. 1925-91) had a master’s degree in planning from the University of Chicago. She proposed and conceptualized the New Bombay plan along with Charles Correa and Shirish Patel. But if you hit up Google with the search “who planned New Bombay,” you have to read the fine print to spot this woman architect’s name.

Gira Sarabhai (1923-2021) was a self-taught architect. By all accounts an excellent one, she has path-breaking institution buildings and other great design projects to her credit. But probably the only time you hear her name is when Le Corbusier’s Villa Sarabhai is in discussion.

Hema Sankalia (1934-2015), Hema Patel (1942-) of Baroda, Madhu Sarin (1945-), and many more. The underlying hint in the previous paragraphs is not a hint, it’s the loudest statement – women architects do not get the respect, admiration, attention, or mention they deserve. Only in the 21st century, long after many of them have passed away, have we begun to hear a few echoes of them here and there.

These are the shadows of the past. Let us now turn our eyes and ears to the light of the present.

Two women architects in the contemporary scene

In this part of the article, I share a brief outline of two contemporary women architects to understand the stand of the women’s movement in modern times.

Anupama Kundoo (1967-)

Anupama Kundoo is a true international architect. However, she still has her Indian touch. Educated at the Sir J.J. School of Art in Mumbai, Kundoo graduated in 1989. Her career is full of meetings with great and sensitive architects. In Kundoo’s third year, she met Laurie Baker and his words were a source of inspiration for her. A year after graduating, she wound up in Auroville with a commission of a house from a French man called Pierre Tran.

From 1992 to 1996, Kundoo was busy with a Berlin-based architectural practice. In 1996 she returned to Auroville and joined hands with some friends to create an organization called Kolam. After several years working at Kolam, Kundoo started her individual practice. She has also worked on the Auroville planning with architect Roger Anger of France. She’s also designed and been involved in multiple housing projects at varied locations.

Kundoo’s awe at the Golconde House by Antonin Raymond in Pondicherry is expected given her involvement in Auroville. She thinks this project exhibits a lot of sensitivity regarding its site, context, climate, and the nature surrounding it. Le Corbusier is also a favorite of Kundoo’s as is Ray Meeker, a ceramist in Pondicherry.

Architectural practice isn’t all Kundoo’s got up her sleeve. She is also engaged in teaching, writing, and research. She has taught at the Parsons New School of Design, New York, University of Queensland in Australia, and has been the chair for Environmental Technology and Material Science.

Married to Luis Feduchi, an architect from Spain, Kundoo is also the mother of two children. She got her Ph.D. from Habitat Unit, Technical University Berlin in 2008 when her children were young which allowed her to stay at home more. If multitasking’s real, Kundoo’s a master in it.

Mona Doctor-Pingel (1967-)

Mona Doctor-Pingel was not into architecture during her years at CEPT University. Only when she underwent practical training in 1987 with German architect Poppo Pingel was her passion for architecture born. Doctor ended up marrying Pingel after five years of their acquaintance.

After practical training, Doctor-Pingel left for Germany to study “Appropriate Rural Technology and Extension Skills” at Flensburg University (that’s just a complicated phrase meaning sustainable technology). In this course, the concept of building biology snatched her attention. This term analyzed the impact of the built environment on the health of the people and the planet.

Now, Poppo Pingel was based in Auroville and had a good architecture firm up and running when he and Mona were married. He was 25 years older than her. All these gaps meant good things and bad. The good thing was that someone was always available to Mona for great advice. The bad news was she was neither taken seriously nor given enough credit for her work. However, as she made a name for herself, these negative attributes slowly weaned off.

In 1995, Doctor-Pingel set up her own practice, an act that Pingel supported, while sharing office space with her. In 2008, she built her own office, making her truly independent.

The biggest influence on Doctor-Pingel was her exposure to Auroville’s architectural atmosphere. This is not the place where the speed of construction and the end value of the building are the sole purposes of architecture. Here, Doctor-Pingel had the opportunity to explore and experiment.

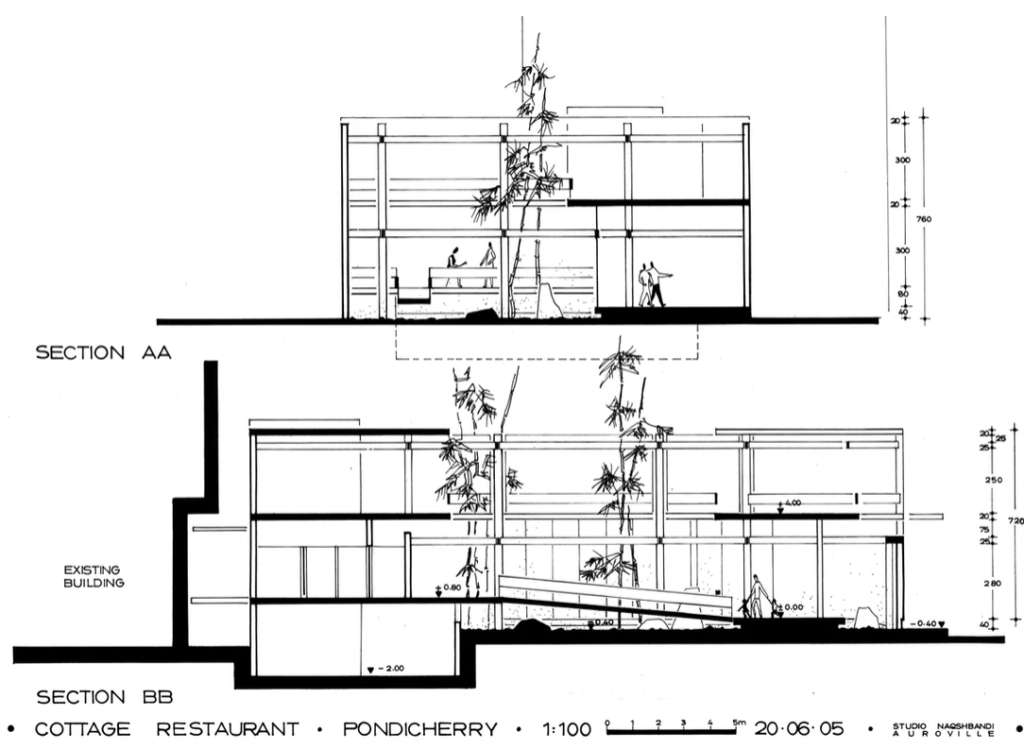

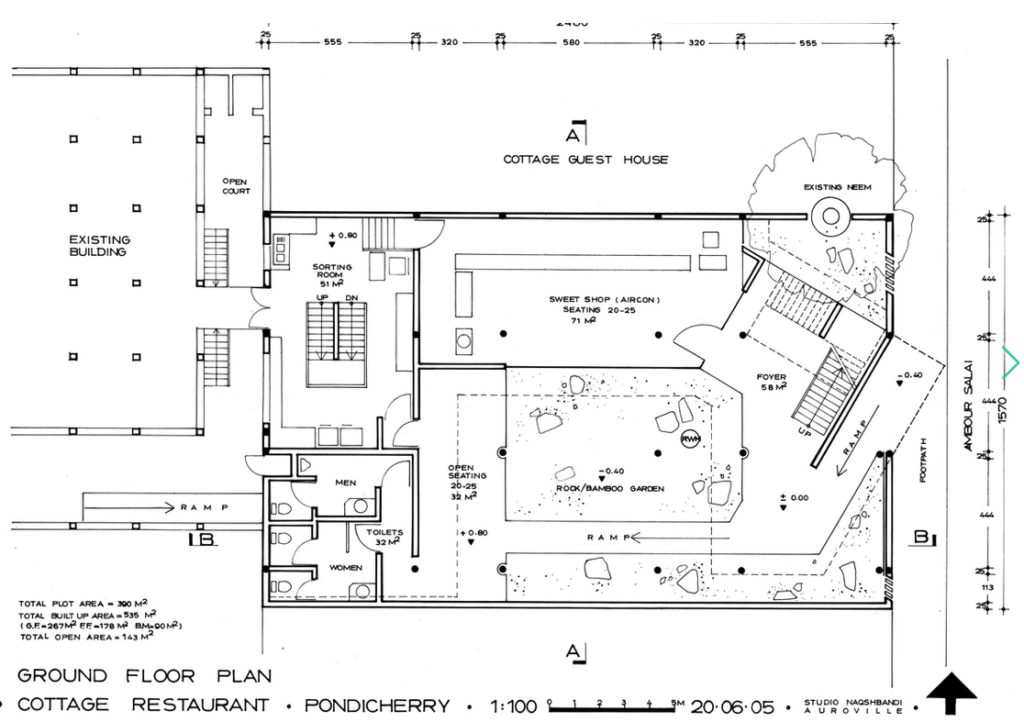

One particular project of Doctor-Pingel in Pondicherry caught my eye – the Cottage Restaurant for the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. It is a restaurant started by The Mother of the Ashram in 1954. This project is not simply a building but an embodiment of the emotions and experiences of the Ashram’s workers. In my opinion, justice has been done to the spiritual atmosphere of the Ashram.

Based around a courtyard, the Cottage Restaurant somehow creates a barrier between the noisy outside world and the calm atmosphere of the interior. The first manifestation of this phenomenon is the angled entrance of the restaurant that betrays no sign of the functions housed within while exuding irresistible mystery.

Once you step into the boundary of the restaurant, the first encounter is with the courtyard of yellow and black bamboo and large pebbles. One glance and you can easily make out the sequence of activities. To your right is the restaurant and to your front is the open seating. From here, you have two options – either you order something at the restaurant and then have your meal inside or in the open, or walk over the ramp right in front of you to the open sitting to simply enjoy the ambiance.

The aesthetics are modernist yet somehow articulated in just a way that they exude a sense of calm beauty so appropriate for the Ashram’s ethos. The concrete structure is fully exposed. Bare, slender beams run a little below the ceiling from round column to round column. The proportions of structural members convey a sense of scale and rhythm that one comes across rarely. The frameless glass panes have been minimally and strategically placed such that every space feels extremely porous and connected.

Doctor-Pingel exhibits quite clearly that it is not a person’s gender but the involvement in a project that produces great architecture.

Thus continues the saga of the women’s movement in the architecture industry. While many milestones have been reached, some distance is yet to be traveled.

I really recommended the book Women Architects and Modernism in India: Narratives and Contemporary Practices. You can check it out here.

Let’s keep this discussion open-ended and hear something about the role and relation of women in architecture from you.