“Good architecture should be resilient,” says David Basulto, founder of ArchDaily, in a video by DW Euromaxx. As vague sentences go, this one takes the cakes. Resilience is one of those words that gets thrown around in architectural discourse without anyone understanding what it means. But as it turns out, it is an important word, especially in the “sustainability” discourses. Understanding this concept can serve to address major unprecedented concerns the world faces, allowing us to fulfill our duties as architects to Mother Earth. So what exactly is resilience in architecture? Why is it necessary? Will using it frequently make someone sound smarter than they are? Let’s try to answer all these questions and initiate a discussion within ourselves.

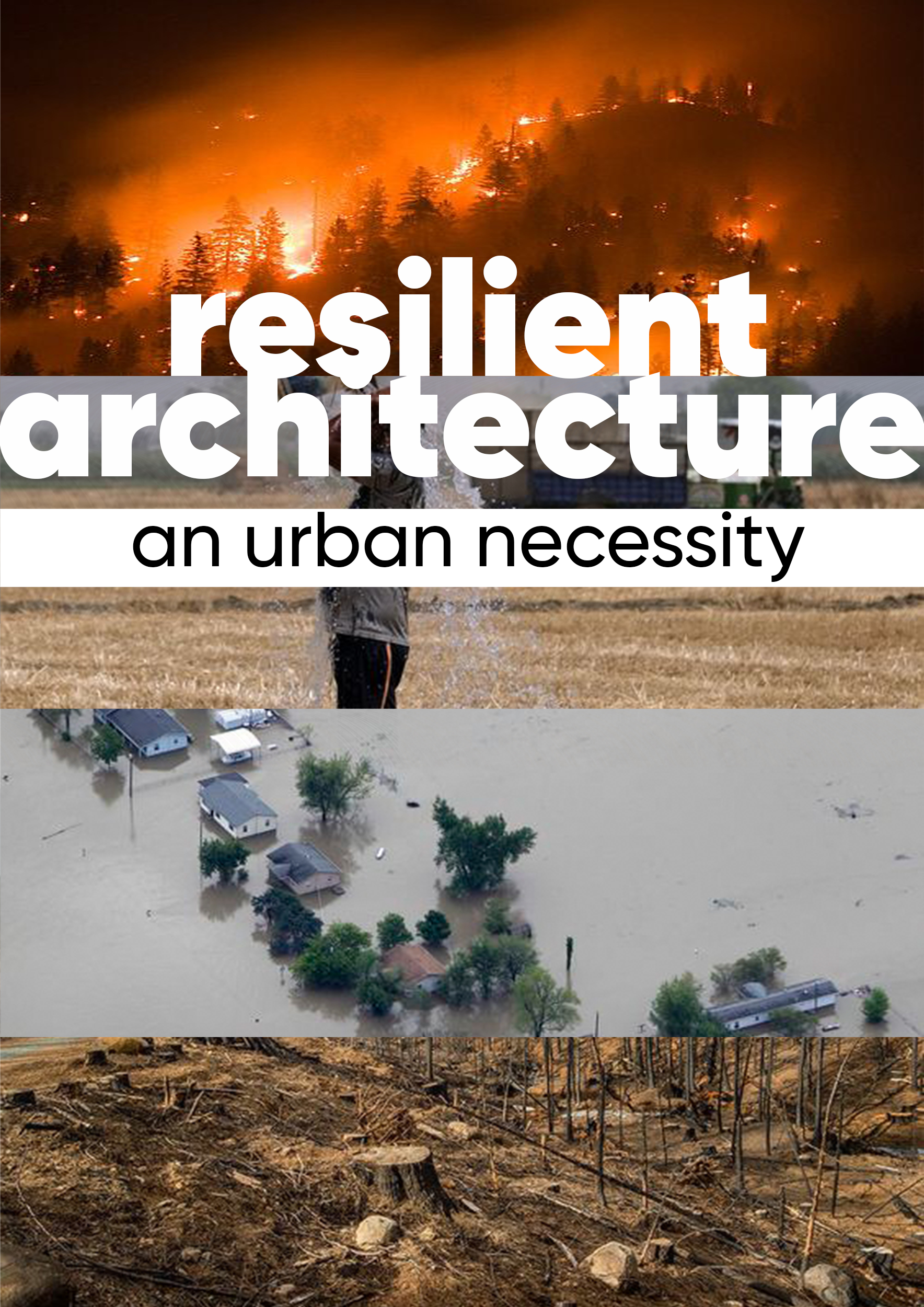

Resilient architecture: What and why

If a human being is resilient, then they are “able to recover quickly after something unpleasant such as shock, injury, etc.” Well, the meaning is more or less the same when applied to the design of buildings or architecture. Resilient architecture or design is the application of ” strategy to enhance the ability of a building, facility, or community to both prevent damage and to recover from damage,” according to the Whole Building Design Guide.

Where does this damage come from? From natural or man-made disasters. Natural disasters include hurricanes, flooding, heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, landslides, etc. Man-made disasters include terror attacks, etc. Evidently, the single most important commodity in such times is a safe shelter. That is where architects jump into the picture. Without proper infrastructure, disasters have the potential to wipe out communities and leave countless people mourning the loss.

It is a general fact that our generation has an overload of information in almost all fields known to humans. Useful in our case is the data from the meteorology department. By studying it, we can predict weather patterns and to a surprisingly large extent, safeguard against several natural disasters.

But why is it that this need for resilient design has been voiced in this day and age with this much fanfare and never before. Well, it is not that communities of yore did not battle with harsh climate and weather. However, never before has climate change been as severe as it is now. And this is a huge factor in the occurrence of natural disasters, the evil from which resilient architecture is the savior.

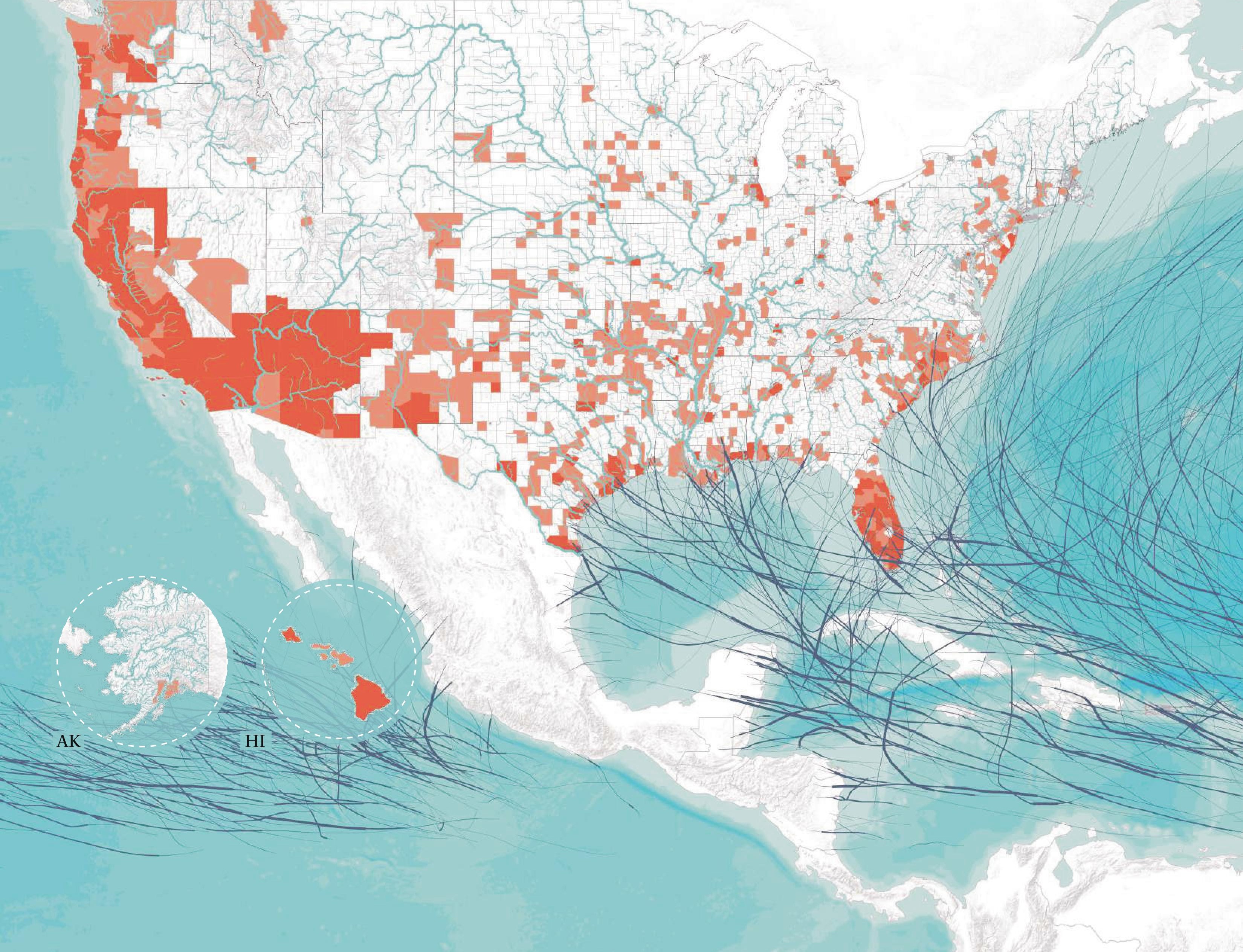

It seems almost comical that a few degrees of heating of the earth’s atmosphere can lead to such large-scale destruction. But it’s true. Due to global warming, the sea is rising, putting at least 570 cities and around 800 million people at risk. Sea level rise also results in soil salinization, rendering it barren and the area prone to droughts and wildfires. Hurricanes have become more frequent, especially along the United States coastlines.

Of course, we cannot leave unmentioned the paradox of the urban heat island. Due to soaring temperatures, urbanites dial down the thermostats to cool off, leading to a higher production of global warming gases. Subsequently, the temperature rises further, and the only option is, of course, to install more air conditioners.

Resilient design does not do away with the physical and mental stresses on a community in times of disaster. However, it does lighten them. And that regard, it is of utmost importance, both in its ideation and implementation. This article cannot contribute much towards the latter side, but maybe it could do some good for the former.

Here are some strategies that may be implemented in times of natural disasters. You can check out this document for more details.

1. Extreme heat (heat waves)

2024 was an exceptional year for heat waves. They were rampant in all parts of the world. New Delhi, India recorded the highest temperature of 53oC, the hottest in 120 years. For cities, the urban heat island effect worsens matter morbidly.

How can design help us mitigate the effects of heat waves? Architects can adopt several strategies. We list some of them below. However, this is by no means an exhaustive list.

- Green/white roofs: Green roofs are roofs with plants on top to provide shading. Doing this can lead to a major reduction in the cooling load or provide much thermal comfort during blackouts. Alternatively, white-painted roofs are also effective. This strategy also greatly reduces the need for mechanical cooling. Not only roofs but any external building element may be painted white.

- Reducing hardscape surfaces: Paved and impermeable surfaces are one of the major causes of the urban heat island effect as well as groundwater repletion. By reducing such surfaces, or making them permeable, much mitigation of heat waves is possible. The Dutch city of Arnhem included this in their list of strategies to combat extreme heat.

- Shading public spaces: Shading is an age-old trick to seek shelter from the sun. That is because it works. Shading playgrounds, parks, natural water bodies, parking, etc ensures that remain functional during extreme temperatures.

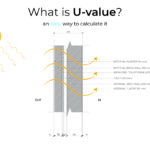

2. Hurricanes and flooding

As it happens, Egypt is among the top flood-risk zones in the world, despite most of its area being desert. The river Nile is the source of livelihood for the farming community while also posing threats to their life. Talk about a complicated relationship. Rising sea levels are also a cause of flooding. As for hurricanes, no one can forget the constant battles the coasts of, for example, United States, among others, have been fighting.

The major problem is damage to infrastructure and the subsequent resettlement issues. One major cause of this echoed all over the world is that the old building bylaws in application could not have accounted for climate change, hence leaving the buildings at all but the mercy of nature. In response to this, many nations have begun revising their building regulations.

Long-term mitigation of flooding and hurricanes must address climate change. However, no one can stop climate change with local action and while we have global verbal agreement on such measures, implementation of them is still far off. For immediate relief, such local measures are necessary.

Speaking from a design perspective, there is only one principle for strategies against hurricanes and flooding: create as many buffers as possible. These buffers have taken several forms.

- Dunes protection and restoration: Stabilization of neglected dunes along coastlines through natural vegetation is a good measure. Where natural dunes are not present, man-made ones may be implemented. These can have many different layers placed successively or one on top of the other or both.

- Creation of water-land features: Water-land features like trails, parks, etc. have the double benefits of acting as a buffer for flooding and providing recreation spaces for residents.

- Limiting building in flood-prone areas: Prevention is better than cure, and in this case, unbelievably so. If flood-prone areas had the least amount of infrastructure, damage would be the least as well as easily handled.

3. Tornadoes and earthquakes

Fortunately, there is more awareness around earthquake-resistant buildings than, say, a decade ago. Modern building technology performs reasonably well during earthquakes and tornadoes. Structurally speaking, both of these hazards exert lateral or horizontal loads on a building so designing for one usually suffices for the other as well.

The main damage from tornadoes or high-speed winds comes to structurally unstable buildings mostly in rural areas. Open spaces and community shelters are the best infrastructure for the aftermath of such disasters.

- Community centers: For those whose homes have been destroyed or have been rendered uninhabitable by the disaster, this is an essential commodity.

- Building code compliance: Most modern codes stipulate earthquake-resistant designs. Buildings must comply with the local regulations.

- Public spaces to be kept clear: Public gathering places like parks, playgrounds, etc should not be used for debris.

4. Wildfires

The Americas have the highest occurrence of wildfires in the world. High temperatures and dry weather are the leading cause of this disaster. The fire takes out the trees and destroys the shelters of the wildlife. However, the smoke is more lethal, killing humans and animals alike. Combine that with the current amount of pollution in the air, the smoke is doubly hazardous. Along with that, wildfires are huge CO2 emitters.

Heat waves, droughts, and wildfires are connected phenomena. The appearance of any one signals the others are trailing behind. Huge wildfires leave acres of land barren, disrupting transportation, communications, water supply, and power and gas services. The widespread disturbance of a wildfire was amply showcased in the Australian bushfires of 2019-20.

Design against wildfires involves creating a distance between combustible items and dwellings as well as clear evacuation routes.

- Constructing fire-smart homes: Fire-smart homes reduce the risk of damage to houses and the spread of fire. Strategies involved in such homes include storing combustible services, like gas, away from the core of the house, keeping the grass short, pruning trees, etc.

- Maintaining fire breaks: Fire breaks are spaces of non-flammable materials, like hardscaping, between a potential wildfire site and dwellings. Sometimes, they are just vacant spaces with a small number of carefully selected plants.

- Creating water bodies: This is a disputable strategy because of the amount of water and maintenance required for a man-made water body. Preservation of existing water bodies is much easier.

- Clear evacuation routes: Evacuation routes according to the local bylaws are essential once a wildfire is upon a neighborhood.

These were some preventive measures suggested for particular cases. Of course, resilient architecture is not confined to natural disasters. Any design that respects its environment and seeks a symbiotic relationship with it, rather than against it, is an example of resilient architecture. That means passive design strategies, efficient mechanical systems, carbon-friendly structural systems, etc should all be present in a building.

Another aspect of resilient architecture is that it is a participatory process, and it involves all the stakeholders. Architects, contractors, residents, planners, neighbors, and maybe even the cattle of the place should voice their concerns. After all, resilience is not a universal concept and means different things to different groups.