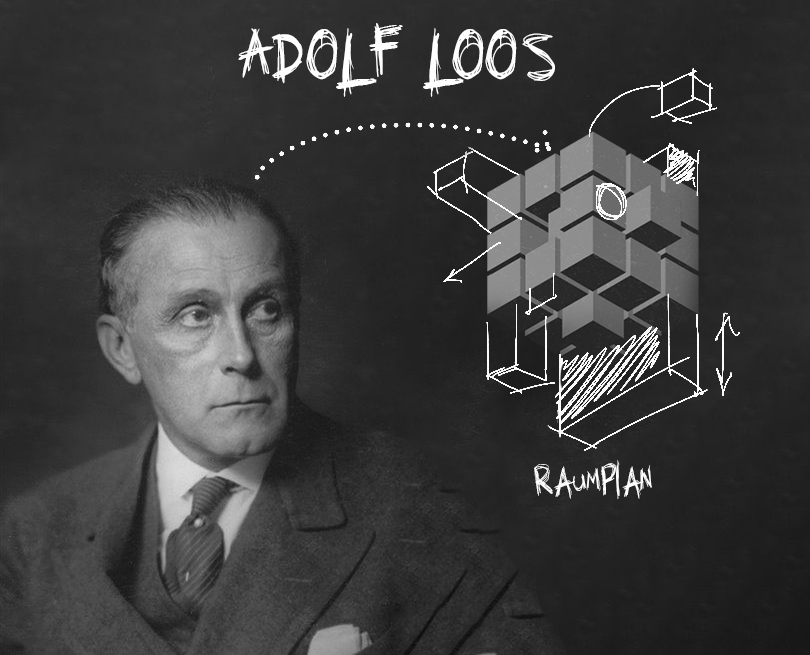

Adolf Loos was a man of many hats, some beautiful, some ugly. Part architect, part critic, part sexual predator, he is an under-recognized presence in modern architectural history. His design philosophy of the raumplan or designing with spaces, as opposed to using a two-dimensional plan, was a truly revolutionary method. It many ways, it contained the germ of the modern movement. While we intend to stick to the professional side of the man, this article would be amiss if it did not foray slightly into Loos’ private life.

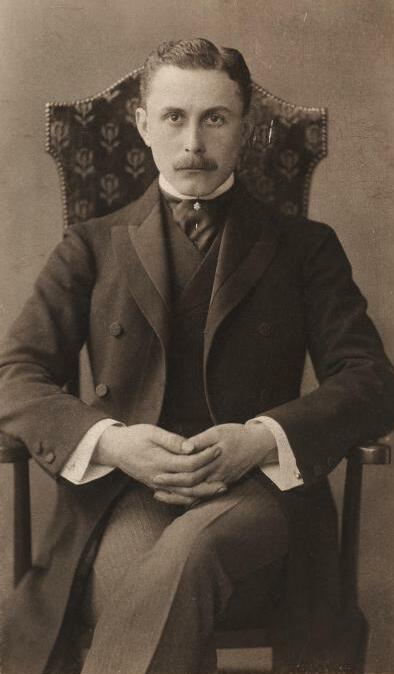

Hence, a few biographical details are in order. Born on 10 December 1870 in what is now Brno, Czech Republic, Loos’ full was Adolf Franz Karl Viktor Maria Loos. His misfortune wasn’t related to just his name. He was also born deaf and regained partial hearing later in life only to lose it totally in his old age. His father was a stonemason, who died when Loos was nine, and his mother had the same profession.

Loos kept switching his education pursuits – first, he studied mechanics, then building technology, then back to mechanics, and finally architecture. In 1893, he moved to the United States and worked as a mason, a floor-layer, and a dishwasher. He first came to New York and then to Chicago. Chicago, the first city where the skyscraper typology emerged, left a huge impact on Loos.

In 1896, he returned to Vienna and stayed there throughout his life. He made pals with like-minded figures but from different backgrounds like music, painting, etc. As far as Loos’ contemporary architects were concerned, he dismissed them all as idiots. In 1903, he designed his first house. He worked mostly within this typology, although he did design some large housing and commercial projects later in his life.

Loos was not the most sexually moral architect. He married three times to women significantly younger than him. These ladies must have seen something in him that the world didn’t, presumably. He was also found guilty of child sexual abuse. Under the pretext of posing as models, he had invited a couple of young girls and exposed himself as well as forcing them to participate in sexual acts. That’s Adolf Loos for you.

All the above comments paint a rather poor picture of Adolf Loos. But let us endeavor to suppress our judgment of the man so that we may examine his sheer architectural genius. In fact, one wonders if all sexual predators have such talent hidden in them, just waiting to be shown the right path.

Adolf Loos’ buildings are something else. His architecture focuses on three-dimensional experience. In a lot of his works, one can detect a reversal of the typical position of the subject and object. The interchange of this basic polarity then carries onto the realm of the private and public, interior and exterior, etc. As a writer, his texts have had enormous impact on the modern movement in architecture and carries relevance even for the present generation of architects.

Let us unpack Loos’ architectural vocabulary through his most famous ideas.

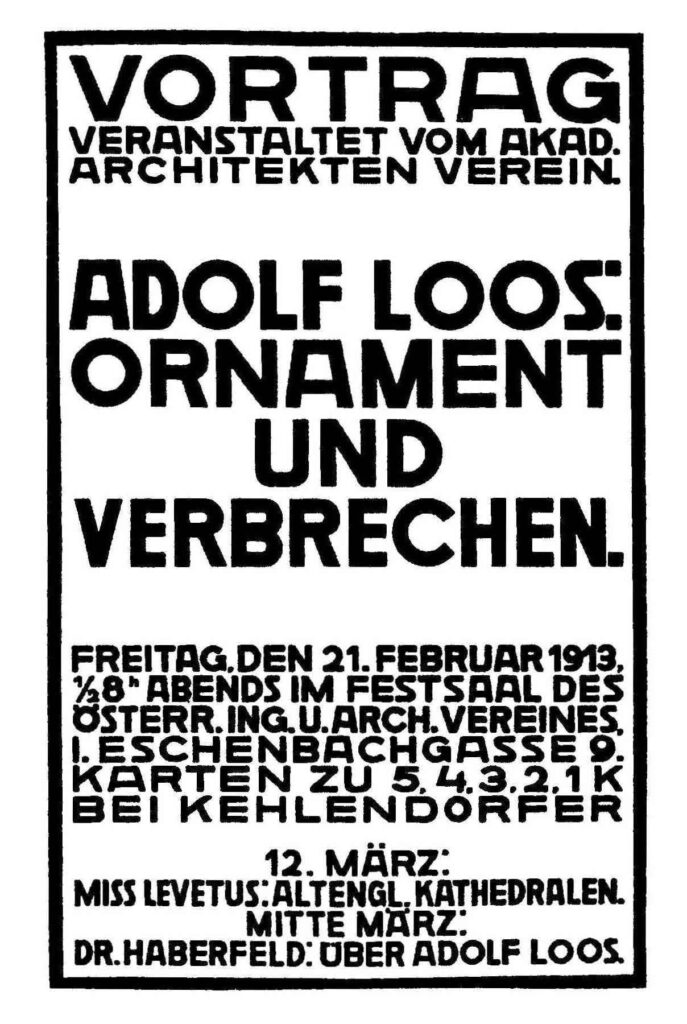

Ornament and crime

People believe Adolf Loos was against ornament of any sort, that all he wanted were whitewashed walls and bare floors. This is absolute nonsense. One look at the rich interiors of his works, like the Villa Muller in Prague, shows Loos’s masterful understanding and sensitivity for aesthetics.

This misunderstanding comes from the essay Ornament and Crime written by Loos and delivered as a lecture in 1910. His words precisely were, “The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornamentation from objects of everyday use.” Nowhere does it say that being modern is equivalent to living in a black-and-white world.

A difference exists between ornament and aesthetic. We live in a culture that is different on so many levels than that of Loos’. In his times, adding random images, mouldings, paintings, and decorations on just about any object that had not the least bit of resemblance to its utility was rampant – the “style” of the artist. In no nice words, Loos struck back at this. The style of the modern world had no ornament, Loos said. This meant any unnecessary fluff that did not contribute somehow to the utility object itself. Meanwhile, this is not to say a plain object has no aesthetics. We will circle back to this in a little while.

Loos’ famous example in this regard was that of a tattooed man. For ancient tribes, tattooing the face was good. If anyone did that now, they were either a degenerate or a criminal. And this went for all objects. Furniture, crockery, clothing, and of course, buildings. There is nothing wrong with the ancients having done ornamentation. It is a crime only for a person of the twentieth century because they are not in keeping with the times.

Loos knew that the way to keep the economy of the nation in the gutter was to keep the senseless ornamentation. A heavily decorated object had no more monetary worth than a plain one. But more hours of work had gone into it. The brunt of this inequality was borne by the producer, the craftsman, who was the underdog. If no one wanted any ornamentation, no one would produce it and hence, the worker could work for fewer hours and yet earn the same. To not do this is a crime against the national economy.

Let us translate Loos’ theory to buildings. A look at the interior of any of his works, like the Villa Muller, Rufer House, or Villa Moller, could throw spectators for a loop. Wasn’t he just calling out artists and craftsmen for being uncultured cavemen? Well, what’s this now? But that’s aesthetics, not style. If you look carefully, there is no superfluous moulding, carving or painting anywhere. What is beautiful is only the material itself. The dark green paint, the brown wooden panels, the marble tiling, etc. Many walls were intentionally left bare to frame the other materials.

(Source: 1, 2, 3, 4)

Loos fancied frosted windows as they acted only as a source of light and provided no view to the exterior. This is because Loos’ design philosophy had a tremendous focus on generating an interior that was as if a world onto itself, distinct from the exterior. We will delve into this in some detail in a while. Sometimes the ceilings had a cladding of panels of a dark material. One anecdote runs like this. An acquaintance of Loos told him that he had a dining room that had a ceiling with dark wooden panels, just like Loos himself often designed. When the architect came to see this room, he said that the ceiling looked disgusting because the height and the position of the room were all wrong.

The underlying motivation of Loos when he equated ornament and crime is ultimately humanist and progressive. To illustrate with Loos’ example, a child involves themselves in activities that they would later consider insignificant. In the same way, the human race itself may have participated in ornamentation once, but now that it had reached the twentieth century, the time had come to abandon such practices.

Adolf Loos’ architecture philosophy – raumplan

If you were to stand on a random street with lines of modern houses stretching out on both sides, you’d not be able to identify a trademark “Loos” building. From the outside, the facade is just like any other house with windows punctured in an apparently random manner. However, if you were to compare the interiors of these houses, there would be a stark difference.

Adolf Loos was nothing short of a master of setting the stage for family life. A house designed by Loos would be a union of polarities – private and public, destination and source, compression and expansion. The public spaces are well-lit, easy to access, and welcoming. As for the private spaces, a visitor, you’d be hard-pressed to figure out the location of the bedrooms. The circulation in Loos’ building is such that spatially, there is awareness of where one came from and where they are headed. And there is lots of play between the sizes of consecutive rooms.

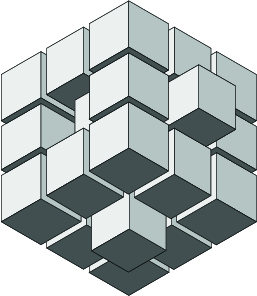

During the first few decades of the twentieth century, two vocabularies of design were prominent – Plan Libre of Corbusier and Raumplan of Adolf Loos. Corbusier said, “Plan is the progenitor.” For Loos, space, or three dimensions, was of paramount importance. In illustrations of raumplan, boxes are stacked on top of one another. Loos always had a space in mind while designing, something to experience and not merely draw as two-dimensional floor plans. That’s why Loos was infamous for not drawing floor plans. He said, “My architecture is not conceived by drawings, but by spaces. I do not draw plans, facades or sections.”

Experientially, this meant almost every room in a house by Loos had a different height even if it served the same function. His designs were always changing mid-construction because he never really knew how a space would be experienced until it was up in three dimensions. Yet somehow, the floor plans had a distinct flavor due to this, many of which were not even done by Loos but by those interested in his buildings. If you have a look at the floor plan of any one of Loos’ villas, like Villa Muller, there are a lot of level differences and stairs to navigate them. You get a sense of the complexity and variety of the space, almost as if it is difficult to determine the exact number of storeys.

Loos believed that a house should be an inward-looking entity and not something that has two-way communication with the surroundings. This was because he thought family life was intensely private and personalized. This is also one of the reasons why he opposed ornamentation. The ‘ornamentation’ house was the very way the family life evolved with the objects in their use.

A lamp passed down through the family, a table with a peculiar drawer, a ceiling fan placed off-center. All of the things were ornamentation in their way and each had a story to tell, contributing to the sense of “homelyness” of the family. To impose a foreign and immovable “style” onto this, something which the family could not relate to, was a crime.

But back to Loos’ obsession with creating an isolated environment for a house. As we mentioned, many frosted windows keep the gaze from wandering out of the house in many places. In this regard, Loos supposedly shared a comment with Le Corbusier, “Loos told me one day: ‘A cultivated man does not look out of the window; his window is made of ground glass; it is there only to let the light in, not to let the gaze pass through.” Related to this is the polarity of subject and object in a house as well as how Loos architecture reverses it.

An example would best explain this. The entertainer of the house is the subject. A visitor is the object. Loos’ design ensures that the object never violates the security and to some extent, the primacy of the subject. The living room’s position does not allow the visitor to peek into the private quarters. Should the entertainer wish to fetch something from the kitchen, the visitor is never out of sight. Only when the visitor makes complicated turns do they arrive at the private spaces of the house, like the bedroom. This is evident in the case of Villa Muller’s living room.

But that’s not all. Just like the master he was, Loos could reserve this polarity at will. The unrealized Baker house, designed for Josephine Baker, a dancer, showcases this talent of his. The central feature of this house is a swimming pool on the second floor with a skylight on top and corridors flanking two sides. There are windows on either side of the swimming pool beneath the water line.

When Josephine entertains a guest at the swimming pool, they become the subject gazing at her body swimming, through the corridor windows. Josephine is then the object. This particular project is different from all other projects of Loos. The design reflects the identification by Loos of Baker as solely an entertainer. Some might say this house is downright spooky. Well, Loos does have some history of sexual immorality, so who knows?

We have already discussed the aesthetics Loos promoted in his architecture. As far as the facade is concerned, we can say that Loos never tried to express individuality through it. They were clean with rectangular punctures for openings and sometimes had balconies or terraces. The real ingenuity of Loos’ design came out in the interior. As he states in Ornament and Crime , for the modern man, “His sense of his own individuality is so immensely strong it can no longer be expressed in dress.” Replace the last word with “ornamentation” and read the statement in the context of architecture.

Personally, I believe the world would benefit much from revisiting the design principles of Adolf Loos. One rarely encounters a sensitivity of such magnitude towards the cultivation of an intensely private family life through architecture. Most residential projects of this era emerge from a flat plan, even though there is variation in the elevation. Ultimately, this affects the experience of the occupants and perhaps may contribute towards binding the failing family structures of today’s society.